The Spectrum 128K and the Inves Spectrum+

On April 20th 1982, Clive Sinclair announced the ZX Spectrum to the world. History doesn’t record the date on which he finally grew tired of the new machine, but it was certainly within that first year.

The actions of Sinclair the company follow closely the character of Sinclair the man, specifically through two distinct traits. Firstly we have Sinclair the inventor, naturally draw to the novel and innovative, but always with the eye of a marketer: the first, the cheapest. Even as it was being created, the Spectrum was far from Sinclair’s main focus. Jim Westwood, the company’s chief engineer and designer of the ZX81, was moved to focus on the flat screen TV project, leaving the relatively junior Richard Altwasser to work on the new machine. Lucky break that this was, it shows where the company’s priorities lay.

Secondly we have Sinclair the gambler1. His game of choice was poker, a game of bluffing. It is clear from the chaos in the months following the launch of the Spectrum that Sinclair Research was not fully prepared. Production was not sufficient to meet demand. And yet the cheques kept rolling in and the company kept cashing them. Delivery within 28 days slipped back to first two months and then three. I can imagine that day-to-day life inside Sinclair during the remainder of 1982 was the kind of seat-of-your-pants environment which would appeal to the adrenalin junky gambler, with Clive called upon to regularly speak to the press and ensure potential buyers that everything was fine. And eventually it was. Everyone who ordered a Spectrum got one. Everyone whose Spectrum arrived broken got a replacement. The business of selling computers fell into a regular pattern. It got boring.

Sinclair’s relationship to the computers he’s best known for is at best ambivalent, even as they brought in the income to allow him to focus on other projects which he found more interesting.

I make computers because they are a good market, and they are interesting to design. I don’t feel bad about making them, or selling them for money or anything, there is a demand for them and they do no harm; but I don’t think they are going to save the world.2

“There weren’t projects within Sinclair to develop the Spectrum further,” Nigel Searle, Sinclair’s then Managing Director, would later admit3. The company would focus its efforts on the flat screen TV and the C5, and on the QL and other computing projects which weren’t the Spectrum. Outside Sinclair, however, things were different. An entire industry had been created around Sinclair’s computer. Software was written, hardware was built, and the machines continued to sell, both in the UK and in other countries.

Investrónica

César Rodríguez González4 was a Spanish emigre to Havana who made his fortune in the textile industry. He returned to his native land ahead of the Cuban revolution and settled in Madrid, where he already had business associates and investments. Among these was El Corte Inglés5, a tailors’ shop which would grow to become a chain of department stores across Spain and Portugal. With this growth came diversification. In 1980, Investrónica6 was formed as a wholesaler of technological products, focusing on textile manufacturing and consumer electronics. Among the products they brought to the Spanish market were the computers of Sinclair Research.

The ZX81 was a hit in Spain as it had been elsewhere. When the Spectrum was announced the interest from the public was there, but Spain would have to wait. There would be no Spectrums the Christmas of 1982. The launch would be delayed due to “technical issues”, Charles Cotton, Sinclair’s commercial director, told Investrónica’s director Ricardo García Gete7. As a last minute stop-gap, Investrónica struck a deal to import Dragon computers, but Dragon Data could not supply as many as the wholesaler would have liked.

The Spectrum would not come to Spain until April 1983, a year after its launch in the UK. When it did, it landed with a splash, announced through adverts aired during the wildly popular Un, Dos, Tres television show8. There were two spots, one focusing on the educational use of the Spectrum, the second on its use as a tool for balancing the domestic budget. Deals with banks across Spain reinforced this serious use and alone lead to 16,000 sales9. The Spectrum sold in great numbers, leading Sinclair to recognised Spain as its number one market outside of the UK.

And then… nothing. November 1984 saw the release of the Spectrum+10, the same 48K machine as was already available, but in a new case and with a new keyboard, to address one of the original’s main perceived weaknesses. Critics were not impressed. “At first glance it may look like a conventional professional keyboard, but a few seconds of use are enough to convince us otherwise.”11 Investrónica would eventually offer the Spectrum+ with the ROM and keyboard localised to Spanish, going directly to Sinclair’s keyboard manufacture, Celluloid AB in Sweden, for the components12. In part this was a move to stem the flow of grey imports from the UK13 which were undoubtedly cutting into their profits, as impatient users stopped waiting for the domestic market to catch up.

The launch of the Spectrum+ was accompanied by adverts touting the machine’s ‘64K’ of memory14, showing that maybe Sinclair had learnt something from their partnership with Timex – the same mathematical gymnastics as gave us the ‘72K’ TS2068. The market was evolving at breakneck speed, with newer, more advanced machines such as Amstrad’s CPC appearing. The TS2068 had disappeared along with Timex Sinclair, seeming to take with it the chance of bring its hardware evolutions to the main Sinclair line. The QL had been met with little interest by the Investrónica representatives who were given an early view of it15, and was showing typical Sinclair tardiness in terms of delivery. There were still a great many Spectrum fans in Spain, but Investrónica had nothing new to offer them.

128K

There does not seem to be a canonical timeline of the Spectrum 128K’s development available, despite numerous interviews with those responsible for its creation, both on the Sinclair Research and the Investrónica sides. The exact time, place, and reasons that development began are unclear.

The most widely cited inciting incident were two Royal Decrees issued during the summer of 1985. The first – no. 125016 – announced on June 19th, covered “peripherals for input and representation of information in data processing equipment” and mandated, along with many other common sense requirements, that keyboards sold in Spain should include those symbols necessary to input the Spanish language. The second decree – no. 121517 – announced on July 17th, was far more controversial. It introduced a tariff of 15,000 pesetas18 on all microcomputers imported into Spain. The Spectrum+, which was manufactured by Timex in Portugal and thus liable to the import tax, was selling for around 30,000 pesetas at the time19.

It is now commonly accepted that the second decree was the result of machinations by Eduardo Merigó20, a former government minister and business man. His company Eurohard had purchased the assets of the now-failed Dragon Data21 and was in the process of moving its factory to Casar de Cáceres, Extremadura22. As Spain’s only domestic computer manufacturer, the resurrected Dragon would be free to take advantage of the home market without paying the tax. The decree did not go unchallenged by the existing import computer industry, and on August 28th, King Juan Carlos – on holiday in Mallorca at the time – signed decree no. 155823, which modified the previous decree to apply only to microcomputers with 64K of RAM or less. Famously this would lead to the Amstrad CPC472, a 464 with an extra 8K RAM chip rattling around inside, part of the machine but not available to the user24. It is unclear who was behind this counter-move – possibly representatives of the newly-burgeoning IBM PC compatible market – but the change did not help Investrónica’s Sinclair business.

The Spectrum – still stuck at 48K – remained liable for the import tax and at a major disadvantage in the market. The question is whether this alone was enough to spur the creation of the 128K, or whether it came about as a more general response to Sinclair’s neglect of the platform. There are a few markers which may allow us to build a timeline. An early version of the Spanish version of the 128K’s ROM25 – both the 48K BASIC and the 128K-specific parts – has been found and dated to April 1985. This is well before the announcement of either the Spanish language support requirement or import duty decrees. Even if we assume that an important industry player like Investrónica would have been forewarned of the upcoming changes, it would be surprising if they had enough notice to be this far along in development.

Rumours of the new 128K Spectrum26 would reach the news stands just a couple of weeks before it was revealed at the SONIMAG trade show in late September27. How close the machine shown there was to the one which would be released to the public that Christmas, or whether it was a fully-working pre-production prototype, is not clear. It wouldn’t be a Sinclair without some smoke and a mirror or two. But the timeline in comparison to the Royal Decrees seem very compressed: just one month after the ‘more than 64K’ reprieve, two since the original decree was announced. I think it is probably fair to say that the 128K was in development before the decrees, not in response to them. On the other hand, the pell-mell rush to bring the machine to market against these tight deadlines might suggests why the project was given the codename ‘Derby’.

Over the subsequent months more details trickled out. The machine would be manufactured in Spain, by Induyco – a fellow subsidy with Investrónica of El Corte Inglés – in Madrid, making it the second Spanish-built micro. Release in the UK would be delayed to the following year. No one was in any doubt as to the reason for this. Contemporary accounts made free mention of the glut of 48K Spectrums still unsold from the previous Christmas. Details of this over-production had been brought to light during that year’s chaotic search for funding to secure the future of Sinclair Research, with multiple potential saviours paraded in the press before bowing out.

The Spectrum 128K

What can we infer about the development of the 128K by looking at the final product?

Externally, the Spectrum 128K largely follows the design of the Spectrum+, using the same enclosure and keyboard as designed by Rick Dickinson, originally for the QL. Investrónica’s in-house industrial designer Guillermo Capdevilla is credited with adapting the case for the 128K28. The most obvious feature of this tweaked design is the ‘toastrack’ heat sink, which internally is bolted to the voltage regualtor.

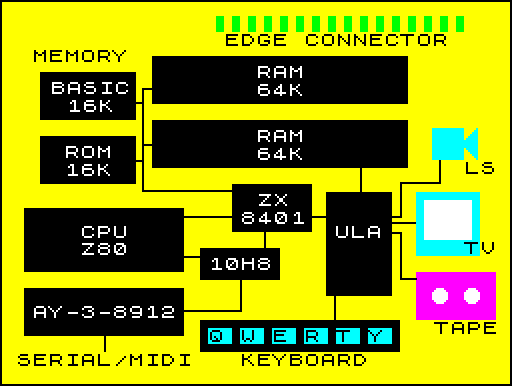

“The design of the [Spectrum 128K’s] ULA, designated 7K010E-5, is almost identical to the 5C and 6C ULAs used in the ZX Spectrum 16/48K,” Chris Smith tells us29. The changes present are firmly geared toward increasing the quality of the video signal. The ULA now produces digital RGB, which feeds both a RGB monitor port as well as standard RF and composite, via a TEA 200030 video encoder. The system is driven by a 17.7345MHz clock to meet the demands of this encoder, and as a result the Z80 runs at a slightly faster 3.5469MHz. These changes seem like perfectly reasonable updates to the Spectrum’s video circuitry, evolutionary upgrades – like that of the keyboard – which could be seen as addressing the original model’s shortcomings, and not specifically geared towards the 128K. The only affordance for the new hardware appears to be the production of a clock signal from the ULA for the AY sound chip.

The major innovations of the 128K – the expanded memory, the sound chip, and the serial/MIDI port – are achieved via an innocuous little chip, the 10H8 PAL, an off-the-shelf component. It works with the ZX8401 and other discrete logic to implement the memory banking and IO port access to the AY-3-8912, through which the serial ports are driven. The ZX8401 is a custom chip made by Texas Instruments, which aggregates the function of a number of discrete logic chips in typical Sinclair cost-saving fashion, and appeared first on Spectrum 48K revision 5 boards.

There were rumours of Timex’s involvement in the design of the 128K. Certainly they had a relationship with Investrónica, who had been selling a version of their FDD 300 floppy drive system in Spain since late 198431 and whose representatives had visited Timex’s Spectrum manufacturing facility in Portugal32. But there seems no evidence of their hand in the final machine. The improved ULA which they inherited from Timex Sinclair with its enhanced graphics modes – which was available in a PAL versions – is sadly absent. The memory banking scheme which the 128K uses is completely different from that employed in the TS2068. And while both systems use the same sound chip – which was very popular at the time and used by many other machines – they do via different IO port addresses33. It’s a small detail, but it would have been a small change which would have promoted some degree of compatibility between Timex’s computers and the official Sinclair line.

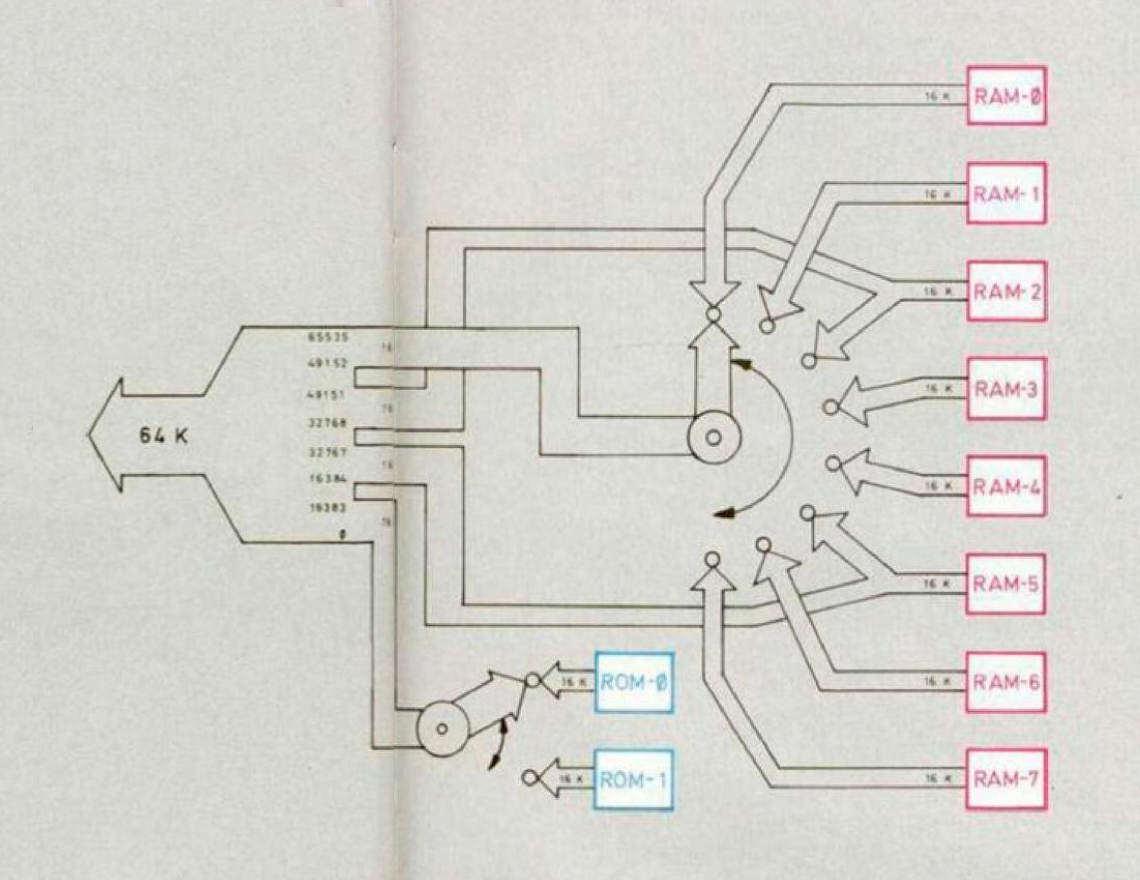

The 128K RAM is divided into 2 physical 64K blocks and 8 logical 16K banks. Any of the logical banks can be paged into the highest 16K of the Z80’s address space (at $C000)34. Bank 2 is always mapped at $8000, and bank 5 into $4000. The ULA can draw the screen from either bank 5 or bank 7, allowing for double-buffering. This means, however, that all banks which share that 64K block are contended, sharing access with the ULA35.

The ROM is 32K, split into two distinct 16K parts – the 128K Editor and the 48K BASIC – either of which can be paged into the lowest 16K. The computer boots into the 128K Editor, which in the original Spanish version is the familiar BASIC prompt, but with a BASIC which has been re-implemented to require each keyword to be entered letter-by-letter, discarding the Spectrum’s unique keyword approach. It includes a rudimentary text editor which uses BASIC strings as storage36. New keywords have been added to access the unique features of the machine, although unfortunately the extra 80K of memory is only available to BASIC in the form of a RAM disk. The PLAY command works with either the AY sound chip or a MIDI adapter plugged into the serial port37. The SPECTRUM keyword takes the user back to the 48K mode for maximum compatibility with existing software, disabling the extended memory and paging-in the 48K BASIC ROM.

Sinclair would update the 128K’s ROMs in preparation for its UK launch. The text editor would be ditched in favour of a menu system, programmed by Rupert Goodwins38, and a number of other bugs would be fixed39. It would be released in January 1986. The first batch of machines were reportedly manufactured in Korea by Samsung40, Sinclair presumably having fallen far out of favour with their UK manufacturing partners Timex, Thorn41 and A.B. Electronics42. Software houses were seeded with the machines pre-launch to ensure that a supply of software which made use of the sound chip and extra memory were available. But despite this promise, the 128K would have the shortest life of all the official Sinclair machines. It was too little too late. In April of that year, the Sinclair brand name and the rights to the Spectrum would be sold to Amstrad. They agreed to take on the 50,000 128Ks which were in the process of being assembled43, but by the end of the year the Spectrum 128K would be gone, replaced that Christmas by the new Amstrad Sinclair Spectrum +2.

In Spain, Investrónica was replaced as official Sinclair distributor by Amstrad’s existing wholesale partner, Indescomp. Bitter reward for dragging the Spectrum forward where Sinclair would not and arguably preserving its relevance so that Sugar could work his cosumer product magic on it. Investrónica would go on to bring the Atari ST to Spain – an announcement made the previous year, alongside the reveal of the 128K, showing that they weren’t planning to keep all their eggs in the one basket – and to embrace the IBM PC compatible. But they were not quite finished with the Spectrum just yet.

The Inves Spectrum+

The Spectrum 128K was an official Sinclair machine, even if it was one seemingly forced upon its reluctant parent company. The Inves Spectrum+44, despite wearing a case from the same official Sinclair moulds and a keyboard from the same supplier, is very much a clone. Released just before Christmas 198645, it was an attempt to retain a foot in the Spectrum market in Spain. There were still many invested users and a large body of compatible software, with a market rejuvenated by budget games especially46. And it was, after all, a market which Investrónica had created. “Based on this fact, Investrónica retains the moral right to perpetuate the Spectrum Plus model, apart from Indescomp, Amstrad and even Sinclair”, declared Primitivo de Fransisco in his review for MicroHobby47.

Unfortunately, for a machine sold on its implicit compatibility48, this is where it fell down49. Over the following months it would slide in the eyes of the magazines from fully-compatible to “halfway”50 to having “serious incompatibility problems”51. It used the same Spanish version of the 48K BASIC ROM as was eventually made available for the Sinclair Spectrum+ and shipped with the Spectrum 128K. Alongside the localised messages and support for extra characters, this introduced a number of incompatibilities. Chief among these was its use of an area of memory which in the original Spectrum ROM was unused and filled with $FF. Many games used this space in setting up a custom interrupt handler, causing them to fail on the Inves.

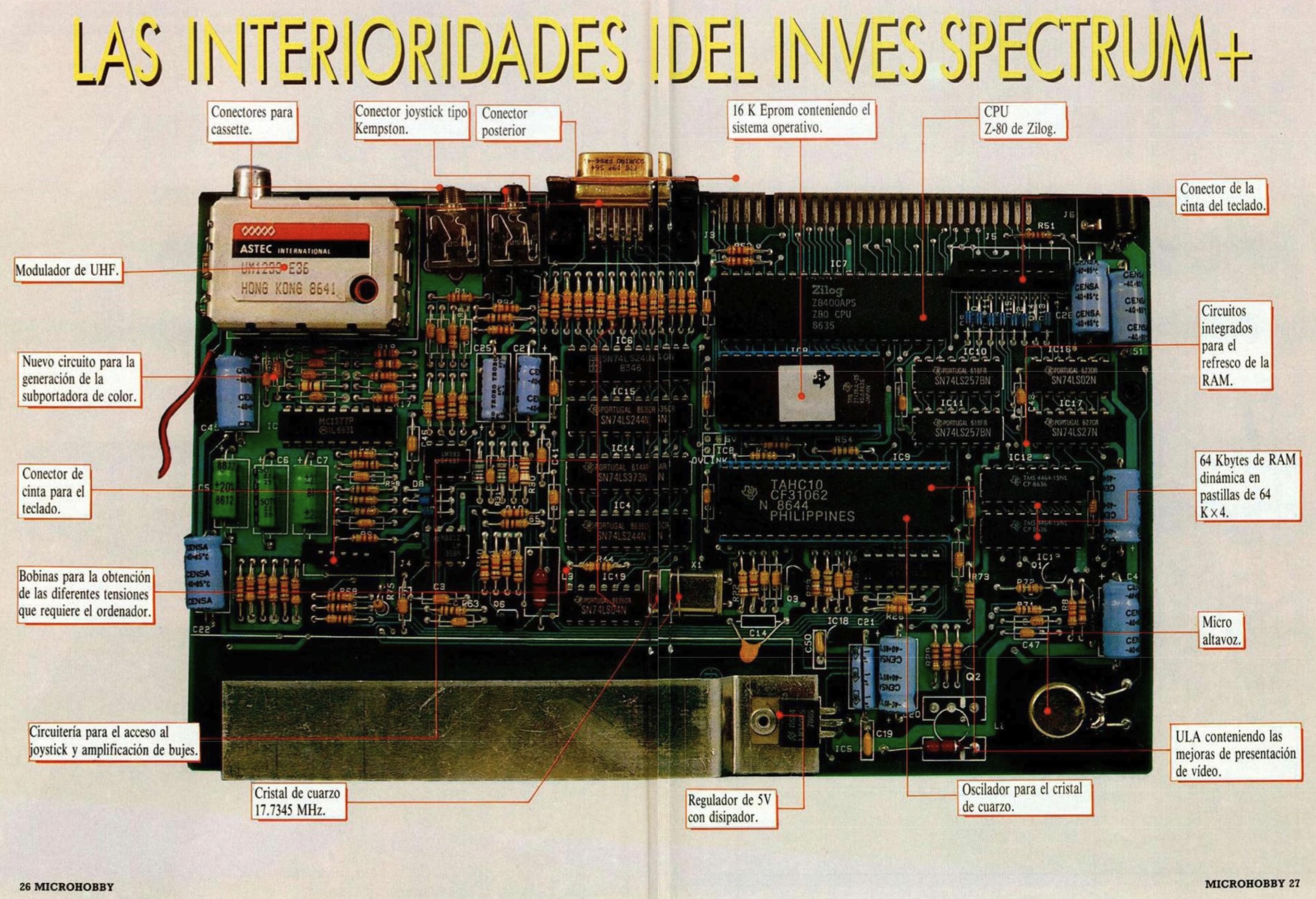

The incompatibilities escalated at the hardware level. This was a Spectrum+ clone, designed to be low-cost. The inclusion of a Kempston-compatible joystick port was as sure a sign of the machine’s intended market as the external keypad of the Spectrum 128K. The machine’s improvements were missing here. Also absent were any official Sinclair components.

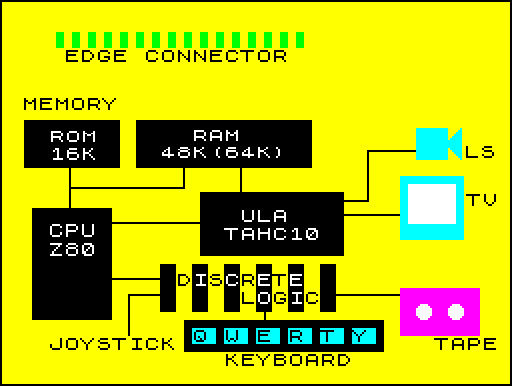

The ULA was replaced by a part designed by Flare Technology52 and manufactured by Texas Instruments using their TAHC10 process. This was a purely digital part with a smaller capacity than Ferranti’s gate array, meaning that some functionality – reading the keyboard and handling cassette input and output – was handled by additional discrete logic. This is a time when genuine ULAs were available for the repair market53, and just a year or so before Didaktik would begin to manufacture the first run of Gamas containing Sinclair ULAs. The TAHC10 used timings which differed greatly from those of the Sinclair Spectrum – specifically around the point at which the vblank interrupt is triggered – meaning that timing-critical code did not run correctly.

Elsewhere, the hardware is a mixed bag. There is 64K of RAM, with the lower 16K inaccessibly behind the ROM54, but there is no contention for access to it. The Z80 CPU runs at the slightly faster 3.54Mhz of the Spectrum 128K. There is the built-in joystick port. The keyboard is as good or bad as that of the Spectrum+ and 128K.

I’ll leave the final words on the machine to Miguel Ángel Rodríguez Jódar and César Hernández Bañó, whose excellent post-mortem of the Inves Spectrum+ is linked from the ‘Resources’ section below:

It is a machine that gives the impression that it has been made with a good idea on paper, but a hasty implementation that has not allowed time to test the machine. … Showing the black points of the Inves Spectrum+ “in the past”, with today’s technology, leaves the work of those engineers in a situation that, for me, is unfair.

Most Spectrum clones were developed in countries where ideas like intellectual property and copyright were strange, foreign concepts. Spain in 1987 – a newly-fledged member of the European Union – was not such a country. While the matter never reached court55, its likely that lawyers’ letters were exchanged. Whatever their moral right, Investrónica’s infractions were blatant and untenable. The Inves Spectrum+ would disappear from sale and Investrónica would move on with the Atari ST, the NES, and its IBM PC clone business.

Resources

-

Noel’s Retro Lab looking at the Inves Spectrum+ part one, part two.

-

Fred Harris reviews the Spectrum 128K for BBC Micro Live.

-

The Retro Shack with an impeccably-researched video on the 128K.

Notes

-

As told by Nigel Searle https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=acuGRFKBqHQ. ↩

-

Practical Computing magazine, vol.5, no.7, July 1982, via https://worldofspectrum.net/CliveSinclairInterview1982/index.html. ↩

-

Interview in Time Designs magazine, vol.4, no.6. ↩

-

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/César_Rodríguez_González_(empresario). ↩

-

El Mundo del Spectrum interview with Ricardo García Gete Investrónica, the Spanish pulse of the Spectrum, part one. ↩

-

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Un,_dos,_tres..._responda_otra_vez. ↩

-

Investrónica, the Spanish pulse of the Spectrum, part one. ↩

-

Spectrum+ preview, MicroHobby, no.1, p.12, November 5th 1984. ↩

-

Spectrum+ review, MicroHobby, no.2, p.26, November 13th 1984. ↩

-

https://medium.com/@uto_dev/the-awakening-of-the-spectrum-128k-3732c7377788. ↩

-

“Sinclair points out” that Investrónica is the only official retailer of the Spectrum in Spain, ZX Magazine, no. 14, p.32. ↩

-

eg. Investrónica advert MicroHobby, no.2, p.20, November 13th 1984. ↩

-

“When we left there, the feeling of all of us who left, of all of us, was that it was not well polished. We left with a bad taste in our mouths.” Ricardo García Gete, interview with elmundospectrum.com. ↩

-

eg. https://auamstrad.es/curiosidades/amstrad-cpc-472-en/ and https://www.amstrad-noob.com/2021/10/12/a-closer-look-at-the-amstrad-cpc-472-timeline/. ↩

-

https://elpais.com/tecnologia/2019/12/02/actualidad/1575302981_189309.html. ↩

-

What You See Is What You Get, Alan Sugar. ↩

-

eg. ZX Magazine, no. 22, September 85, p.9 and MicroHobby, no. 44, 17th-23rd September 85, p.4. It’s interesting that both credit both the news and the development of the 128K to the UK. ↩

-

Investrónica, the Spanish pulse of the Spectrum, part two. ↩

-

How to Design a Microcomputer, Chapter 24: “ULA Versions”. ↩

-

As the Invesdisk 200, announced at SIMO ‘84. ↩

-

Described in Investrónica, the Spanish pulse of the Spectrum, part two. ↩

-

Compare Spectrum 128K Technical Reference and The TS2068 Technical Reference. ↩

-

For more information and a better diagram see http://www.breakintoprogram.co.uk/hardware/computers/zx-spectrum/memory-map. ↩

-

Odd-numbered banks 1, 3, 5 and 7, although the original Service Manual states 4, 5, 6 and 7. ↩

-

Watch the Spanish version of the text editor in action: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_5TKCPrKEzo. ↩

-

https://medium.com/@uto_dev/the-awakening-of-the-spectrum-128k-3732c7377788. ↩

-

https://museum.wales/collections/online/object/9ee50464-a33e-3c8b-8445-48a93df19356/Computer/. ↩

-

What You See Is What You Get, Alan Sugar. ↩

-

https://www.elmundodelspectrum.com/la-rebaja-de-los-videojuegos-a-875-pesetas/. ↩

-

Most of this section comes from http://www.zxprojects.com/inves/, with my own errors added. ↩

-

Comment by Miguel Ángel Rodríguez Jódar (@zxprojects, mcleod_ideafix) on https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J62X4x7mDXo. Flare Technology was staffed by ex-Sinclair employees and would go on to design the Jaguar for Atari. ↩

-

Spin spin spin goes Sir Clive. ↩

-

As far as I can tell from my research. ↩