ZX Spectrum Clone, United States, 1983

Timex

The company which would eventual become Timex Corporation began in 1854 as the Waterbury Clock Company1. They specialised in producing domestic alternatives to the expensive European clocks and pocket watches of the time, manufacturing both for themselves and on behalf of others. They changed owners and name many times over the subsequent 100 years. The 1950s saw the company – now the United States Time Corporation – returning to their roots as a supplier of inexpensive and reliable timepieces. Using the techniques they had developed in the armaments industry, they combined simplified design, newly-developed materials, precision tooling, and automation to produce a reliable and cost-effective product. These skills and experience were in demand, which saw Timex simultaneously expand as a manufacturing sub-contractor to others. From 1945 they manufactured cameras for Polaroid. They expanded with factories across Europe and Asia in addition to the United States.

Timex Sinclair

The histories of Timex and Sinclair meet in the Scottish town of Dundee, where Timex assembled the ZX81 for Sinclair. By the start of the 1980s Timex’s consumer wristwatch business had been feeling the pressure from cheaper Far Eastern manufacturers for some time. Computers seemed like a natural area for them to expand into. From Sinclair’s point of view, having a partner to shoulder the costs associated with breaking the American market, where they already offered limited mail-order sales, offered nothing but advantages. It would be a brief and ill-fated partnership.

Timex Sinclair’s first product – the TS10002, a slightly-modified ZX81 with NTSC video support and 2K of RAM – was announced3 on April 20th 1982. Three days later, Clive Sinclair introduced the ZX Spectrum to the world. For a watch company, Timex had pretty lousy timing. A cynic might also wonder how this was allowed to happen. Surely someone on the Timex side must have been aware that Sinclair’s announcement was imminent, if only because the Dundee factory had been preparing for production of the new machine4.

TS1000

The TS1000 was released in July 1982. Aided by the low price, an extensive advertising campaign, and generally positive reviews5, demand was high. Timex Sinclair would lean heavily on the ‘first computer under $100’ shtick. It wasn’t a lot of computer, but it wasn’t a lot of money, either. The issue of Byte which reviewed the TS1000 listed it for sale at $89, alongside the Atari 400 for $249 and the VIC-20 for $189. 600,000 TS1000s had been sold by the end of that year6 – a claimed 30% of all home micro sales – placing it joint second with the Apple ][ behind the VIC-20’s 750,000. 70,000 of these sales came via an agreement with American Express7. The TS1000 was inducted into the Smithsonian Institute’s permanent collection8. By whatever criteria you wanted to measure it, the TS1000 was a success.

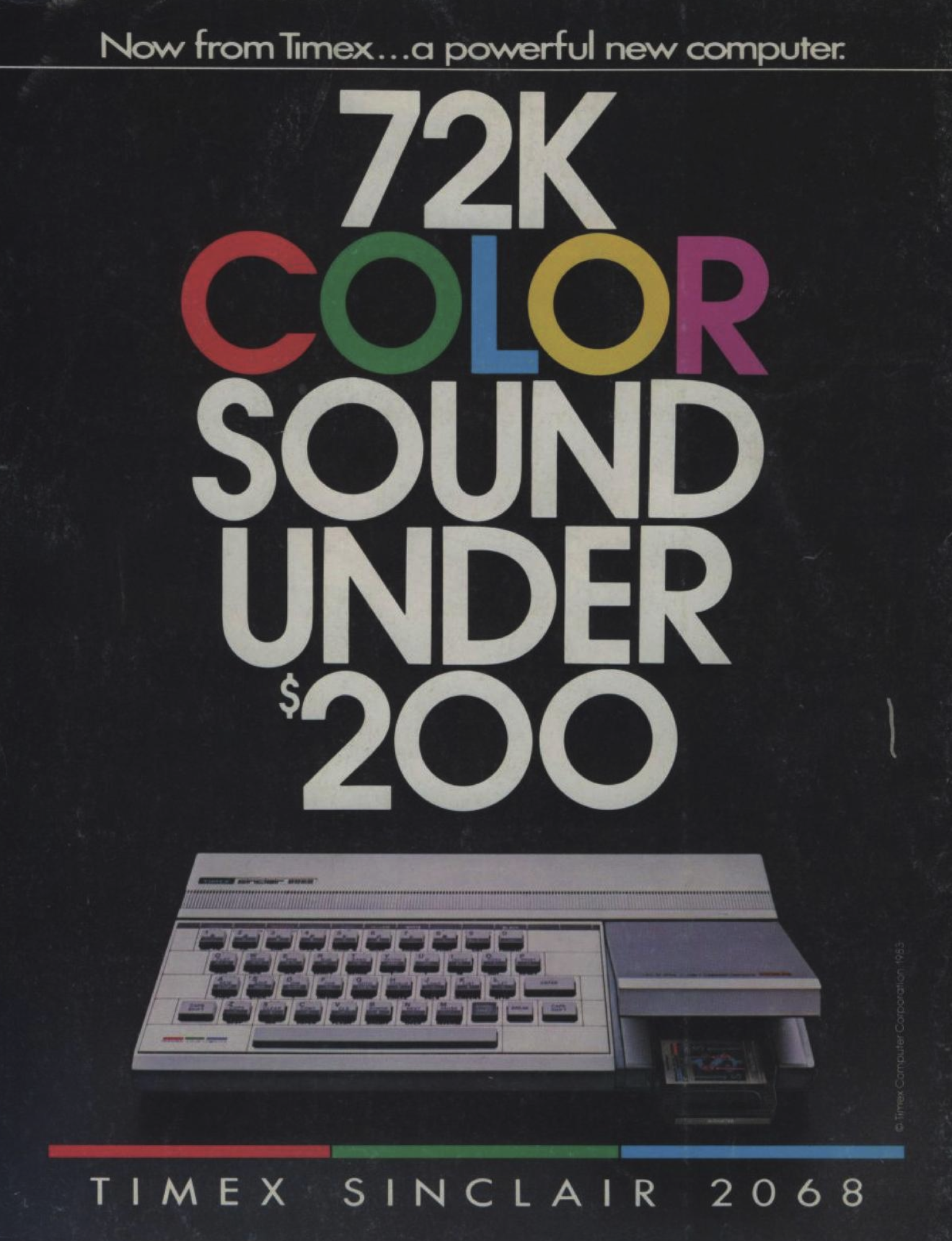

Many business textbooks have been written on the subject of following-up a successful product. There is universal agreement that what you don’t do is tease a bigger and better replacement before you have it ready to go. At the January 1983 CES in Las Vegas, Timex Sinclair announced the TS2000 series9, widely dubbed ‘the American Spectrum’. They would have much improved graphics and sound. A cartridge slot would alleviate the woes of loading software from tape. Bank-switching would allow for up to 16Mb of memory. There would be the 48K TS2048 for $199.95 and the 16K TS2016 for $149.95. It had been an almost-certainty since its launch in the UK that Timex Sinclair would release their own version of the Spectrum, but the way the announcement was handled seemed poorly judged. Sales of the TS1000 instantly declined. By March 1983 some retailers were offering it for a fire-sale $49.95.

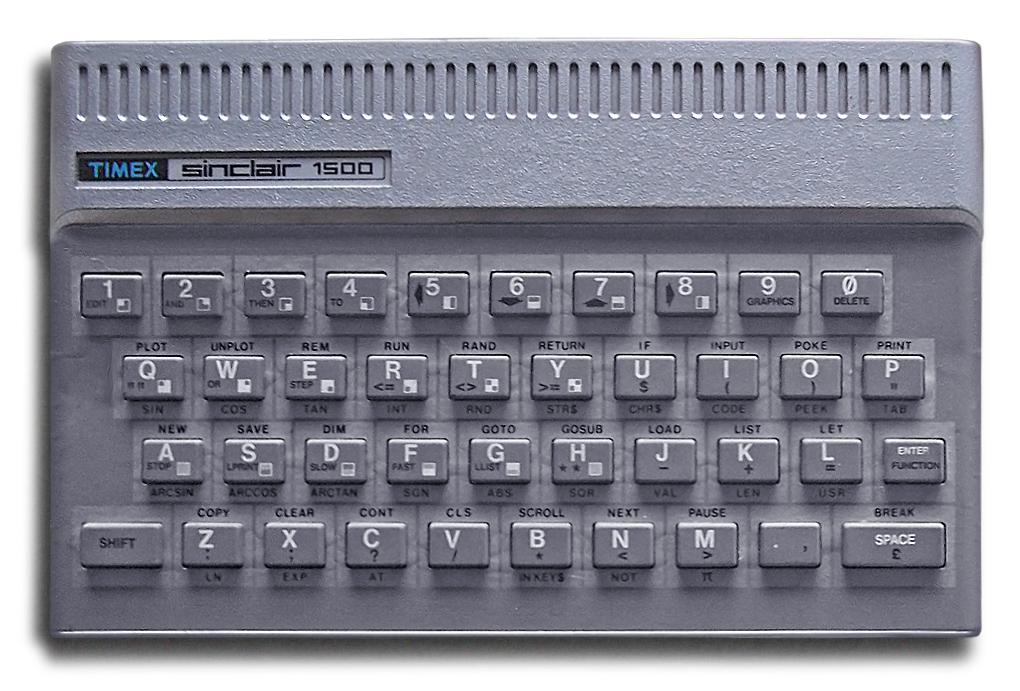

To muddy the waters further, rumours of another Timex Sinclair machine soon began to circulate. “Confusion seems to be the order of the day at Timex,” one editorial observed10. The TS150011 was said to be a TS1000 with 16K of RAM. “We haven’t announced any product like that,” said Dan Ross, Timex Sinclair’s Chief Operating Officer, in an interview with Timex Sinclair User12. The same issue carried its officially announcement13.

The TS1500 went on sale in June 1983. Enclosed in a case almost identical to the Spectrum’s, that would be the only thing it borrowed from Sinclair’s more recent machine. Inside the TS1500 was basically a cost-reduced version of its predecessor. The Ferranti ULA had been replaced by one manufactured by NCR, and as predicted RAM had been increased to 16K, but otherwise it was the same silent, monochrome machine. Even as the first 16K computer for under $80 it was met by general bemusement.

TS2068

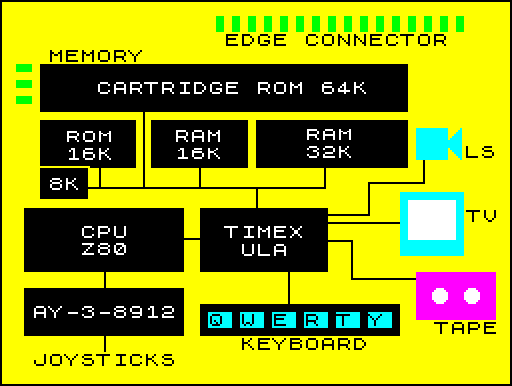

The TS2000 series would be released in November 1983 in the form of a single 48K model, the TS206814. To write it off as merely ‘the American Spectrum’ would be a mistake15. While not exactly revolutionary, the TS2068 took a number of evolutionary steps, some of which it would take the official Spectrum years to catch up with – and some which it never would in its lifetime – and all just a year and a half after the Spectrum’s launch. The TS2068 included an AY-3-891216 sound chip; the Spectrum wouldn’t get the same until the Spectrum 128K two years later. There were two joystick ports, one on either side, read via the sound chip and not following either the Kempston or any of the key-base schemes. The keyboard was an improvement, if for no other reason than it had a full-size space bar.

Externally, besides the keyboard, the most obvious change was the cartridge port, concealed under a flap to the right. It is said to have been added due to the machine’s designers’ frustration with loading software from cassette17. Each cartridge can hold up to 64K as eight 8K banks which can be mapped individually into the Z80’s address space.

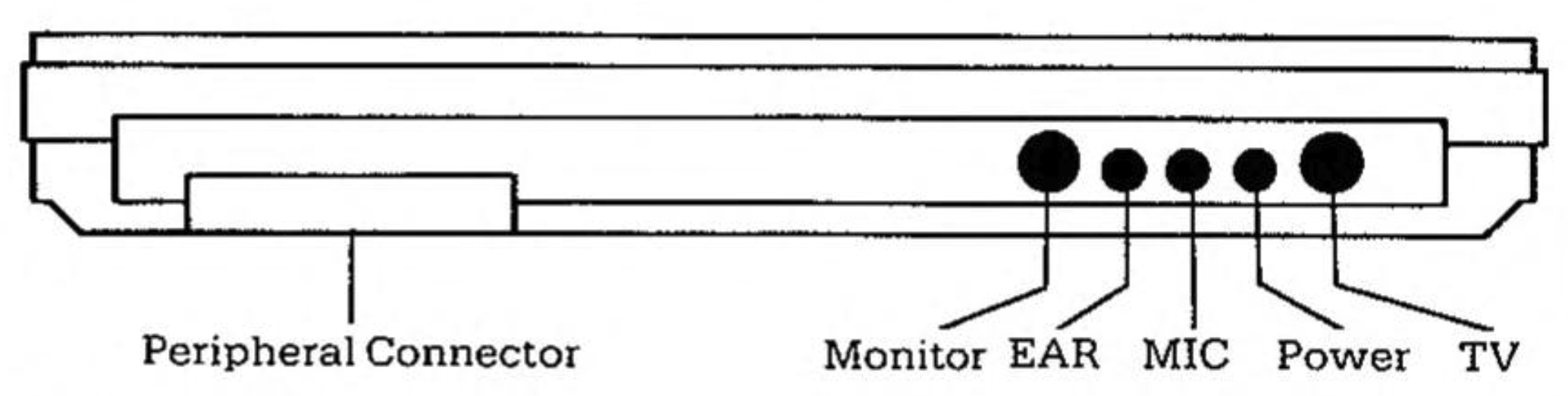

On the rear of the computer, from right to left, are RF out – there’s a channel selection switch on the underside of the case – power, cassette in and out, composite video out, and an expansion connector behind a cover. The expansion connector is not compatible with the one on the Spectrum.

Inside, the heart of the machine is a SCLD (Standard Cell Logic Device18), the TS2068’s version of the ULA, performing all the same functions as its Spectrum counterpart, along with managing the additional bank-switching features. Contemporary reviews credit the chip to NCR (National Cash Register) Semiconductor, although later machines would contain chips bearing the Ferranti Portugal mark.

Turning the TS206819 on – without a cartridge installed – we are greeted by a pair of copyright messages, one for Sinclair and the other Timex.

What should have been the biggest new feature of the TS2068 over the Spectrum was the introduction of the ‘enhanced display’ modes. The regular 256 by 192 pixel, 32 by 24 character colour screen was supplemented by three new variants. All used an extra 6912 bytes of memory. The first simply added a second identical screen, which would allow double-buffering – drawing into the ‘off screen’ memory while the ‘on screen’ was being output to the monitor, a technique used by games to reduce the flickering which could occur when attempting to update display memory while it was being drawn. The other two were far more interesting.

‘Extended color mode’ used the second bank of display memory to hold an attribute byte for each byte of pixel data in the first, meaning separate colour attributes could be specified per 8x1 pixel cell, rather than the standard 8x8. Decades later, clever hacks like the BIFROST* Engine20 would manage to replicate something similar with the original Spectrum hardware, albeit only in a sub-area of the screen and at a major cost in terms of performance.

‘Full width mode’ produced a 512 pixel, 64-character-wide display. Pixel data for alternate columns was drawn from the first and second display memories in turn21 and output by the video system at twice the pace of the other modes. “64 characters, plus two 8 character-wide margins exactly fills a standard 80 column format page for word processing applications,” says the manual22, in an attempt to persuade us we didn’t really need 80 columns. Along with the improved clarity of the composite output this would have been a boon to professional software, if only the number of programs which used it had been larger. Among the number which did not was the TS2068’s own in-ROM BASIC. It would take a heavily-patched version, in the form of Zebra’s OS-6423, to fix this issue.

The state of the TS2068’s ROM in general was indicative of a development process which ran out of time, despite pulling in such big guns as The Complete Spectrum ROM Disassembly author Ian Logan24 to help. There were the kernels of some good ideas, innovating on the Spectrum ROM on which it was based, like the ‘function dispatched’ which provided a stable API for calling in-ROM BASIC routines from other languages. But for every improvement there was a regression. No longer able to fit within 16K, bank-switching – still heralded by the user manual as giving access to 16Mb of memory – was used to juggle between the main BASIC ROM and the 8K Extension ROM, mapped into the start of memory. Marketing would total these, and along with the 48K RAM would declare the TS2068 a 72K system.

But by far the TS2068’s ROM’s biggest short-coming was its lack of full compatibility with its British cousin. This would soon come in the form of build-it-yourself projects which would allow for the installation of the ROM from the 48K Spectrum, either internally or via the cartridge slot, some purportedly based on Timex’s own planned “Chameleon” Spectrum emulator cartridge25. “All the software that we envisioned when we originally purchased our 2068s is available NOW if you have the Spectrum ROM,” wrote one reviewer26. Similar hardware fixes for the incompatible expansion connector were equally quick to appear.

Ultimately, whatever its advantages or disadvantages, the TS2068 never really got a chance to prove itself in the market. In early 1984, barely four months after its release, Timex would bow out of the computer market altogether. The world never got to meet the TS306827. The partnership with Sinclair was ended, although it’s probably reasonable to assume that it had been strained for some time. No matter how apathetic Sir Clive may have been to the Spectrum by this point, Timex’s announced intention to ‘improve’ it for the American market must have rankled – no matter that it became necessary after Sinclair’s own NTSC version of the ULA failed FCC testing. Sinclair is known to have declared that Timex has “fouled up” the Spectrum28. There was probably also some small amount of schadenfreude that it was the time and cost of this re-engineering which would ultimately majorly contribute to Timex Sinclair’s downfall. Which is a shame, since the TS2068 contained the germ of many good ideas, which if given a little extra time to mature could have formed the basis for at least a Spectrum v1.5. Unfortunately, the only thing Sinclair seemed to take from their partnership with Timex was the TS1500’s innovation of re-launching the same old computer in a shiny new case.

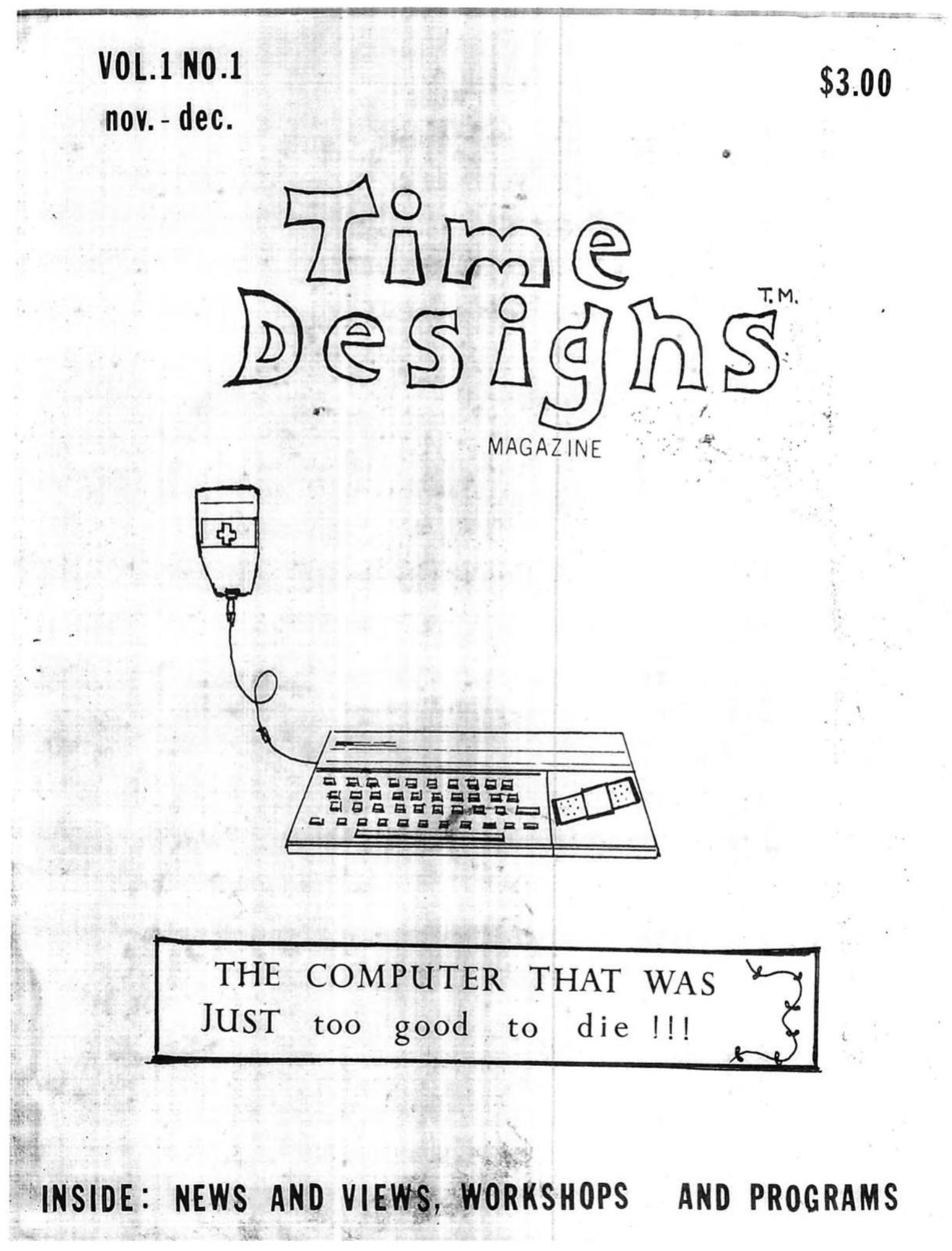

But this would not be the end of the road for the TS2068. The machine would live on in the hearts and minds of its users, who through magazines and user groups would keep its spirit alive, and chronicle the trickle of new software and hardware released for it. More practically, the TS2068 would continue to be produced on the other side of the Atlantic.

Timex Computers

The history of Timex Computers – as Timex’s Portuguese subsidiary would come to be best known – is a story for a different article. Suffice to say that it was chosen to manufacture the TS1500 and TS2068 for sale in American, and continued to do so after Timex Sinclair’s withdrawal from the market. Portugal was the one Western European market which the deal with Sinclair has ceded to Timex. Renamed the TC2068, the TS2068 would continue to be sold here in two forms. The first came in a black case, bundled with the TimeWord29 word processor, which made full use of the 64 column ‘full width’ display mode. The other – the “Silver Avenger”30 – apparently under no misapprehension about its intended use, came bundled with a Spectrum ROM cartridge. Both models featured redesigned main boards with fully Spectrum-compatible extension connectors31.

The Portuguese market wouldn’t be the end for the TC2068, either. It was sold into South32 and Central America33, back into the US in a small way34, and into Poland. The Unipolbrity 208635 would eventually be assembled in Gdańsk from components imported from Portugal, combined with a better keyboard36. These too were accompanied by the Spectrum ROM emulation cartridge, and while it’s good to know that the TS2068 lived on, at least for a little while, it’s sad that it was mainly while pretending to be a lesser machine.

The TS2068 is a story of missed opportunities. In a parallel universe, the Spectrum+ contained a sound chip and a couple of enhanced graphics modes inside its shiny new case.

Resources

-

timexsinclair.com is an amazing treasure house of material.

Notes

-

The machine is variously referred to as ‘T/S 1000’, ‘TS 1000’ and ‘TS1000’. I’ll stick to the later, and apply the same to other Timex Sinclair machines. ↩

-

https://ia802909.us.archive.org/35/items/sinclair-research/Sinclair_Press_Releases.pdf ↩

-

A really cynical cynic might suggest that preparation for production of the Spectrum had yet to begin at the point Sinclair started taking orders for it. ↩

-

eg. Byte, January 1983 ↩

-

Report by Future Computing, Inc. from Byte, March 1983, p.494. ↩

-

Mentioned in Byte, March 1983, p.463. See also the last page of the previously-referenced TS1000 press release. ↩

-

https://www.timexsinclair.com/computers/timex-sinclair-1500/ ↩

-

Lou Galie, SVP of Technology at Timex, claims that Dan Ross misspoke and called the TS2048 ‘TS2068’ and then insisted that the name stayed. Byte High No Limit, Issue 22, p.64 via Wikipedia. ↩

-

It’s a mistake I almost made. This post was going to skip quickly over the TS2068 on its way to more interesting machines. Luckily while researching the short summary I thought I wanted to write I saw my error and so here we are. ↩

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/General_Instrument_AY-3-8910 ↩

-

Lou Galie, Byte High No Limit, Issue 22, p.64. ↩

-

https://www.timexsinclair.com/blog/vlsi-technology-scld-engineering-samples/ ↩

-

In Fuse, in TS2068 mode, because I don’t have access to a real machine. ↩

-

All these modes keep the Spectrum’s basic approach of combining two bytes for each run of pixels displayed, presumably using a variant of the page mode trick. ↩

-

Sinclair Timex User Magazine, vol. 3, no. 1, January 1985(?), p.9. ↩

-

https://www.timexsinclair.com/product/timex-sinclair-3068/ ↩

-

Mentioned in interview with Nigel Searle in Time Designs magazine, vol. 4, no.6. ↩