ZX Spectrum Clone, Czechoslovakia, 1990-1992

The heart of the ZX Spectrum is the ULA, the semi-custom microchip which, among other input-output duties, generates the distinctive display. It is what makes a Spectrum a Spectrum. Most Eastern Bloc Spectrum clones replicate its behaviour with scores of discrete logic chips, with varying levels of technical ingenuity and compatibility. The Czechoslovakian Didaktik company took a more direct route. The Gama was unique in its use of a genuine Spectrum ULA. These were still being produced into the late 1980s to supply the after-market repair industry. The last rolled off the Plessey1 production line in 19892. This left Didaktik with a dilemma: How do they continue production of their Spectrum-compatible computers if they can no longer get the most important component?

A solution would present itself in the shape of Angstrem3, the Soviet semiconductor manufacturer, based in Zelenograd, Moscow. Boris Malashevich, historian of Soviet computing, former Chief Specialist at Angstrem, and “uncle of the domestic microprocessor”4, recounts the story in his article Zelenograd Household and School Computers5, published in 2008:

In 1990, the head of the microprocessor department of [Angstrem’s sister Research Institute of Fine Technology] NIITT P.R. Mashevich was on a business trip in Slovakia6 and saw in the store a Sinclair-like Didaktik Gama computer – a Slovak clone of the ZX Spectrum. At his request, the head of the enterprise where he was … organized a visit to the Didaktik Skalica company. Having familiarized himself with the computer, P.R. Mashevich proposed replacing the medium-integration IC used in it with one semi-custom LSI. Didaktik management met the proposal without enthusiasm, doubting its feasibility, but agreed to try LSI. For the work, Mashevich was given an electrical circuit and a sample Didaktik Gama.

…

Samples of LSI, along with relevant documentation and recommendations for use, were transferred through the embassy to Slovakia … There was no answer for a long time. Later it turned out that the LSI was handed over to the developer [at] Didaktik Gama for testing, but he did not understand it in detail, and after a careless and unsuccessful attempt to use it, he declared the LSI unsuitable for use.

To clarify the situation, P.R. Mashevich and B.V. Ilyichev went to Slovakia, taking with them several samples of their boards. When they were put into computers, they immediately started working without any differences from Slovak machines. As a result, Didaktik Skalica for a number of years became a stable consumer of products from the Angstrem plant, and not only the … controller, but the entire LSI set that grew around it.

So, a heart-warming tale of Soviet engineers helping out their backwards Czechoslovakian comrades with a complex technical problem. But there is an alternative version7 of this creation myth, one which lacks an official publication but is simpler and contains fewer embellishments8:

Victor Klemon, an extremely interesting person and a capable organizer, contacted Soviet developers in 1989 … [who] agreed to supply the kits (ULA + RAM + ROM) for [Didaktik’s] production. Of course, in Zelenograd they produced not an analogue of the proprietary ULA … but their own development based on the BMK … [the T34VG1].

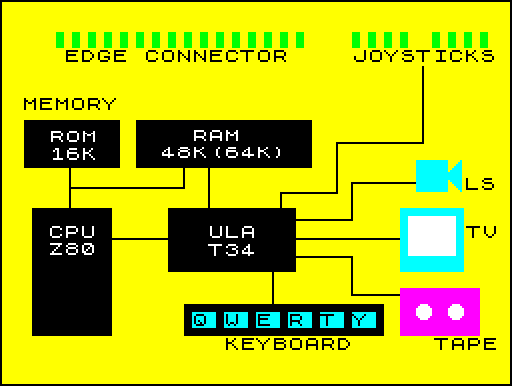

Whichever version contains the most truthiness, the relationship bore fruit in the form of the T34VG19 (Cyrillic: Т34ВГ1). This was an application of Angstrem’s Base Matrix Crystal10 (BMK) (Russian: Базовый матричный кристалл - БМК) technology, a gate array similar to Ferranti’s Uncommitted Logic Array. The T34VG1, like the ULA it was designed to replace, handled video signal generation, clock generation, keyboard reading, tape signal input and output, and beeper audio output. It also had an additional input pin which could be used for implementing extra interfaces such as a Kempston joystick11.

The first micro to contain the T34VG1 would be the Didaktik M, launched in 1990.

Taking a Look

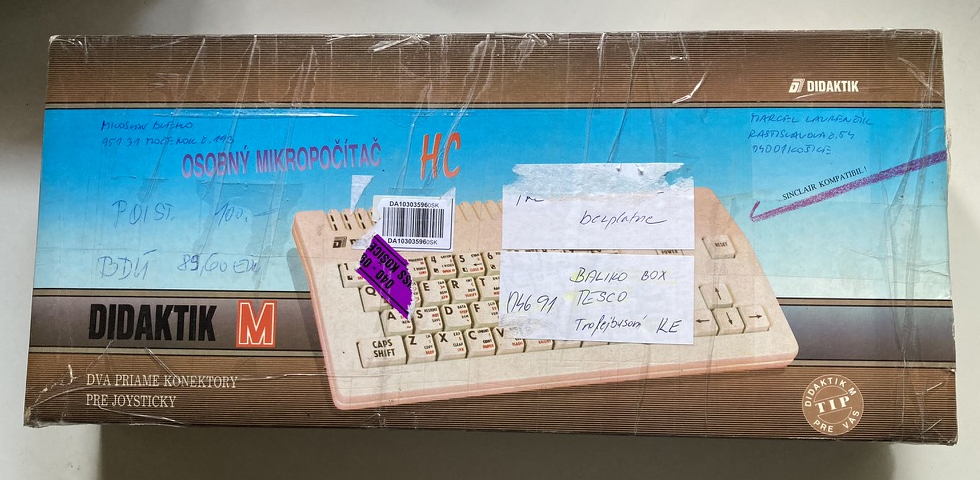

This example is complete with the original box.

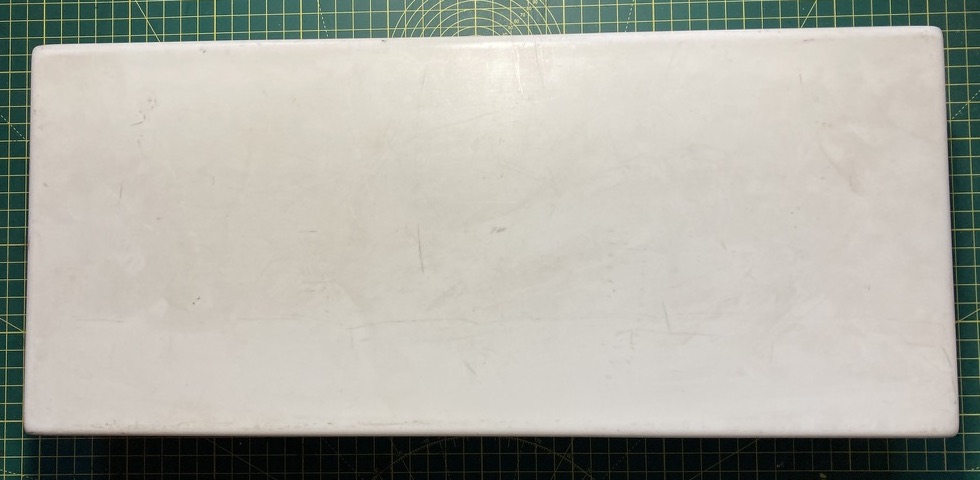

The M is presented in a hard plastic case, similar to the Gama, although longer and slimmer. Inside is the computer and its power supply. The manuals which would originally have been included are not here. I’m trying to track down versions online.

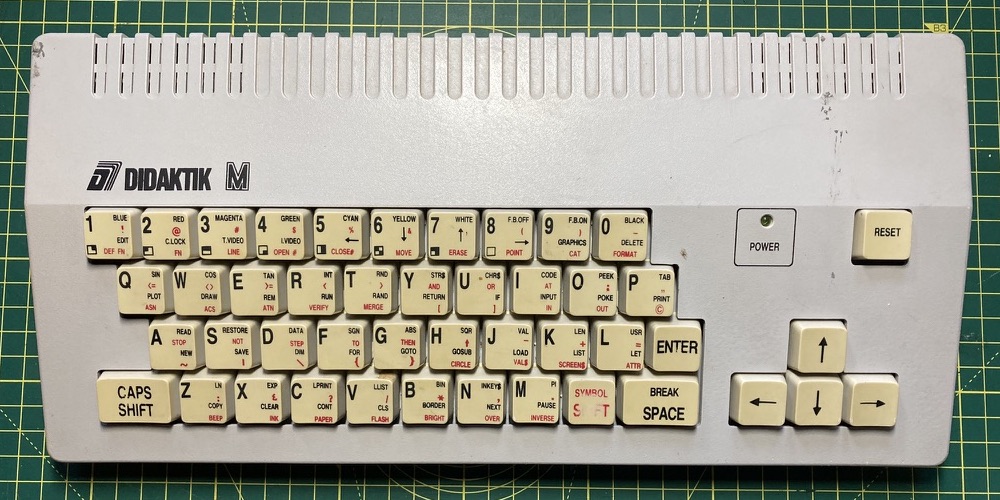

The design of the M’s case is by Marián Višňovský12. In both appearance and manufacture it is light years ahead of most other Eastern Bloc Spectrum clones, and in my opinion is up there with the best-looking of the 8- and 16-bit micros. The keyboard isn’t completely terrible, either. The chunky RESET button requires CAPS SHIFT to be held at the same time to trigger.

On the rear of the case, reading right to left, we have RF and composite outputs; power and cassette (‘mangnetofon’) in; the expansion edge connector, which is almost-but-not-quite compatible with the Spectrum; and edge connectors for Kempston and Sinclair joysticks. The former makes use of the additional function of the T34VG1, while the latter connects via the data lines used by the keyboard matrix.

On the underside of the machine is a paper sticker with a 9012 manufacturing code. I was also surprised to find an intact warranty seal over one of the eight screw holes.

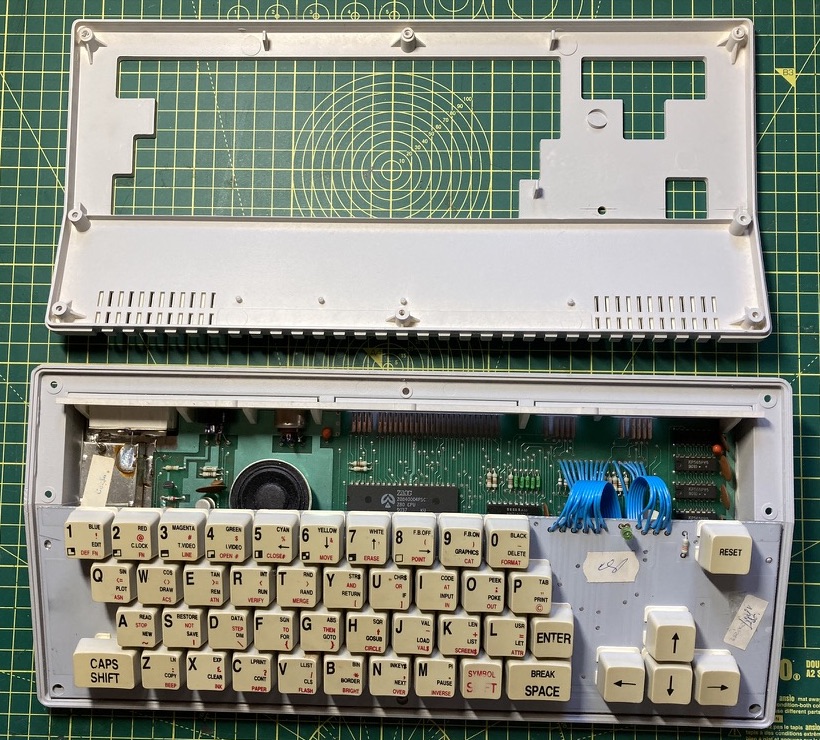

Once unscrewed, the top of the case lifts away, leaving the keyboard in place above the main board, which is another nice indication of the care put into the design.

Moving the keyboard aside, one of the first things to strike you is how uncluttered the motherboard is. In part this is due to the simplification brought by the T34 – here labelled ‘ULA1’ – but also because the M offers fewer extras compared to the Gama. Gone is the 8522 peripheral interface. RAM is also reduced from 80K to just 48K. The eight Soviet “KR565RU5G” (Cyrillic: “КР565РУ5Г”) RAM chips on the right of the board provide 64K, the lower 16K of which is inaccessible behind the ROM.13 Both the RAM chips and the T34 have 9010 date codes.

The CPU is a Zilog Z80, here clocked to 4Mhz, up from the Spectrum’s 3.5Mhz. It has a 9037 date code. The ROM is Microchip branded. There are a few extra Tesla LS logic chips dotted around the board. Video output is managed by a combination of LM1886N – to convert the T34’s digital output to analogue – and LM1889N.

One final observation: the black blob of the T34 is, to me at least, superficially reminiscent of the epoxy-covered NES-on-a-chip found in Famiclones14.

Turning it On

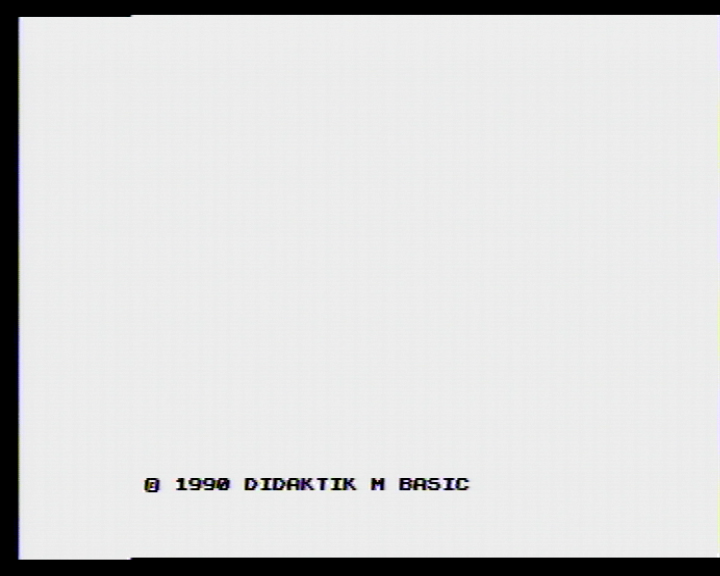

Powering the M on, we see the copyright message “© 1990 DIDAKTIK M BASIC”.

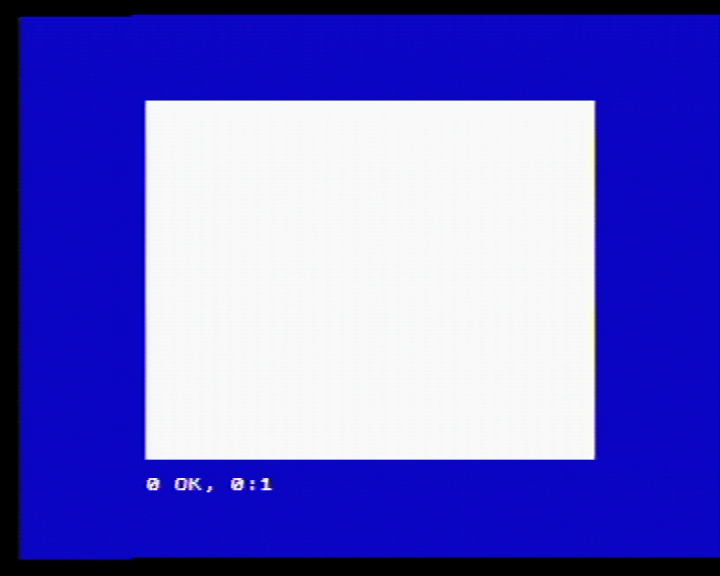

Playing around with the border colour reveals something interesting.

No, don’t adjust your web browser, your eyes do not deceive you, the Spectrum’s 256x192 screen is being drawn as a square.

The eccentricities don’t end there. On paper, the 4Mhz CPU sounds great compared to the Spectrum’s 3.5Mhz. But the T34VG1 was designed in such a way that all memory access by the CPU now face wait times15. In the Spectrum, only the lower 16K containing the screen memory was subject to contention when the ULA would halt it if it attempted simultaneous memory access. Malashevich seems to treat this regression as an innovation:

… video memory, separate and with its own controller in English and Slovak computers, was circuit-technically combined with common RAM with a single controller. The RAM used dynamic memory, requiring periodic regeneration of information. This process is similar to the process of image regeneration on the screen, and they were combined in one device.

The faster processor speed in the M was meant to compensate for this slowdown, and in one respect it does. Running Noel’s BASIC benchmark16 gives a time in the same 87 second region as a genuine 48K Spectrum. But at the same time the faster clock speed introduces incompatibilities with time-sensitive code, such as that which counts instructions and updates the border colours as the screen was drawn.

T34

The designation ‘T34’ was given to the chipset by Angstrem engineer Yu.L. Otrokhov, who served as a tank driver in his youth17. Otrokhov was the chief designer of the T34VM1 (Cyrillic: Т34ВМ1), a from-scratch reimplementation of the Z80 which Angstrem worked on at the same time as the T34VG1, and which when finished just happened to feature the same bugs and errata as the East German U88018.

As with the rest of this history, there isn’t a clear picture of what else Angstrem was working on in terms of microcomputers at this time. Some19 claim that the ‘Zelenograd engineers’ were already working on a BMK-based ULA analogue based on the Baltik Spectrum clone, and that it was this already-completed product which Didaktik saw and chose to use. This would provide a 3rd version of the T34VG1’s creation story. However it happened, by the end of development Angstrem had clones of the ULA and the Z80. With the addition of RAM and ROM20 that was everything you needed to build a computer.

Let’s take a moment to appreciate the accidental aptness of the ‘T34’ name. Designed during the later half of the 1930s, the Soviet T34 tank21, while it contained a few innovations, was not cutting-edge technology. It was designed with the available production capabilities firmly in mind, with cost and speed of production leading factors. The undoubted skill and courage of their crews aside, the T34’s strength lay in sheer weight of numbers. Over 80,000 were built during the course of the Second World War.

Returning to the start of the 1990s, Angstrem’s next move was just good business: they release the T34 chipset (including the ROMs, complete with Didaktik copyright message) onto the rapidly-opening market. As the Soviet Union collapsed, if you found yourself in charge of the necessary facilities with an under-employed staff skilled in electronics assembly, entrance to the home computer business was only an order away. What followed was a Cambrian Explosion of Speciclones, as factories from the Baltic to the Black Sea, from Brest to Izhevska, churned-out their own variants.

These machines were much of a muchness, as you would expect from their common components. They varied only in the cheapness of their cases and the awfulness of their keyboards. If we single any out for special mention it should be the ANBELO/C. This is the machine which Angstrem were working on as the prototype of the T34 machines, either before contact with Didaktik, or while waiting for Didaktik’s approval of the newly-delivered chipset, depending on which story we believe. The instructions which accompanied the completed machine contain the following:

The purpose of this development was to create a new computer element base, which is not only software, but also hardware compatible with computers of this type produced in European countries. The household computer “DIDAKTIK 2”, produced since 1990 and already found in our country, was chosen as the prototype.

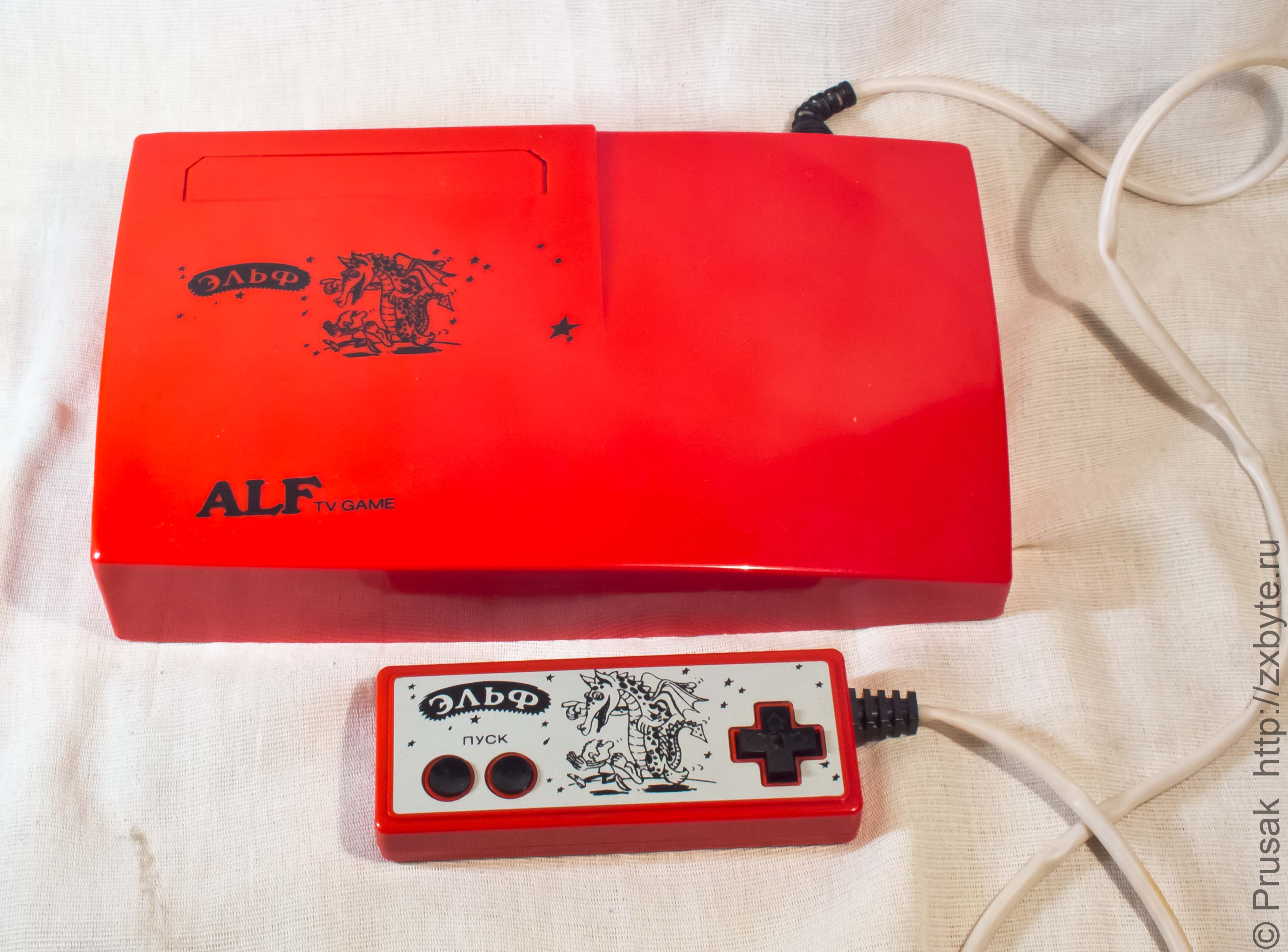

Also worth a mention is the ALF (or Elf) (Russian: “Эльф”) TV Game22. Packaged like a game console, it sidesteps the keyboard problem by having only control pads. Games were delivered via ROM cartridge23. An attempt to counter the influx of Famiclones, the obvious drawback was that Spectrum games had to be adapted to work from cartridge, at a stroke destroying the advantages of availability and price which came with easily-copiable cassette-based games.

Production of the T34 chipset and micros based on it would continue for a few short years, until ultimately a combination of PC-compatibles for serious work and Famiclones – such as the near-ubiquitous Dendy24 – for cheap (and reliable) fun would come to dominate.

Didaktik would release one more home computer using the T34VG1. The Kompact included a 720K 3.5” disk drive. It looked lovely but was too little too late.

Additional Resources

-

Schematics for the Didaktik M (plus many other machines) https://z00m.speccy.cz/?file=hardware.

-

The ‘Clueless Engineer’25 video series on the Didaktik M on YouTube.

Notes

-

Plessey took over Ferranti’s semiconductor business in 1988. ↩

-

The newest E-7 entry in Byte Delight’s ‘ULA Gallery’ has Plessey markings and an 8936 date code. ↩

-

https://www.computer-museum.ru/articles/galglory/4590/ (in Russian). ↩

-

From Электроника НТБ (“Electronics: Science, Technology, Business”), No.7, 2008 https://www.electronics.ru/files/article_pdf/0/article_477_336.pdf via http://155la3.ru/t34vg1.htm. ↩

-

Czechoslovakia will not undergo the ‘Velvet Divorce’ for another couple of years after the time of this story, but as the Czech and Slovak nations had maintained their separate identities throughout the enforced partnership, I think it is valid to describe this as having happened in Slovakia. ↩

-

https://zx-pk.ru/threads/255-spisok-(poisk)-otechestvennogo-speccy-zheleza.html?s=e65d69a5811e9ad6bed30bbbe448824d&p=14131#post14131 ↩

-

“Some factual errors in the article do not allow us to fully trust [Malashevich’s] version” https://speccy.info/Т34. ↩

-

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Т34ВМ1_и_Т34ВГ1 and https://speccy.info/Т34. ↩

-

The /SSRD line. Implementing a Kempston joystick port was easier but not trivial. See https://zxbyte.ru/t34vg1.htm. ↩

-

https://dennikn.sk/287802/skvely-slovensky-pocitac-prisiel-neskoro/ ↩

-

That grinding sound you hear is Sir Clive spinning in his grave at the thought of the extra expense. ↩

-

Comment on https://www.old-computers.com/museum/computer.asp?c=459. ↩

-

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1bfWSR2Ngy1RPedS6j-M607eeAhsd40-nhAfswILzzS8/edit#gid=0 ↩

-

B. Malashevich, Zelenograd Household and School Computers. ↩

-

“It is known that the T34VM1 and subsequent ones, produced in the USSR, contain differences in undocumented commands that exactly coincide with the operating logic of the GDR U880 processor” https://speccy.info/%D0%A234. ↩

-

eg. Comments from https://zx-pk.ru/threads/255-spisok-(poisk)-otechestvennogo-speccy-zheleza.html?p=14131#post14131 (in Russian). ↩

-

Didaktik was already being supplied with T34RE1 (Cyrillic: Т34РЕ1) masked ROMs containing their slightly-modified version of the 48K Sinclair ROM. ↩

-

Banking allows the contents of the cartridge to replace the on-board 16K BASIC ROM. There is also a ‘menu’ ROM on-board. ↩

-

He actually seems to have quite the clue, but what do I know? ↩